Executive summary

During the 2018 general election, Vote Rev collaborated with the state Democratic party in Texas to evaluate a sliver of the Vote Rev program. Vote Rev asks campaign supporters to mobilize their friends to vote. This experiment reached out to randomly selected early voters and measured the effect of that outreach on the turnout of the roommates of those early voters. After collecting official voter turnout records, the experiment estimates that people were 1.1 percentage points more likely to vote after their early voting roommate was sent a text by Vote Rev asking for participation. This result nearly crosses traditional thresholds of statistical significance (p < 0.06) and is nearly four-times larger than the direct effect of sending texts to mobilize voters (roughly, 0.3 percentage points).

Research design

In cooperation with the Texas State Democratic Party, Vote Rev conducted a very light touch mobilization experiment.

Target population

Voters were eligible for the experiment if they met the following conditions:

They had already voted (early) in the 2018 election;

Analytic models predict they support Democrats;

They lived with at least one more registered person who had not voted and is modeled to support Democrats (and no one else who had also voted early);

A reliable cell phone number was available for the voter;

They had not already signed up for Vote Rev through an earlier recruitment effort. The experiment ultimately included 16,626 targeted early voters and their 21,371 roommates.

Randomization

Voters meeting the four criteria above were randomly assigned to the treatment (50%)1 and control groups (50%). After looking at vote history and a handful of demographic variables, the treatment and control groups appear virtually identical for both the targeted early voters and their roommates. Thus, any difference in the turnout behavior of the roommate can be considered the causal effect of the texting program from Vote Rev.

1: Randomization was conducted via simple random assignment and the unit of randomization is the targeted voter.

Treatment

The treatment consisted of two waves of text messages (see the Appendix for examples).

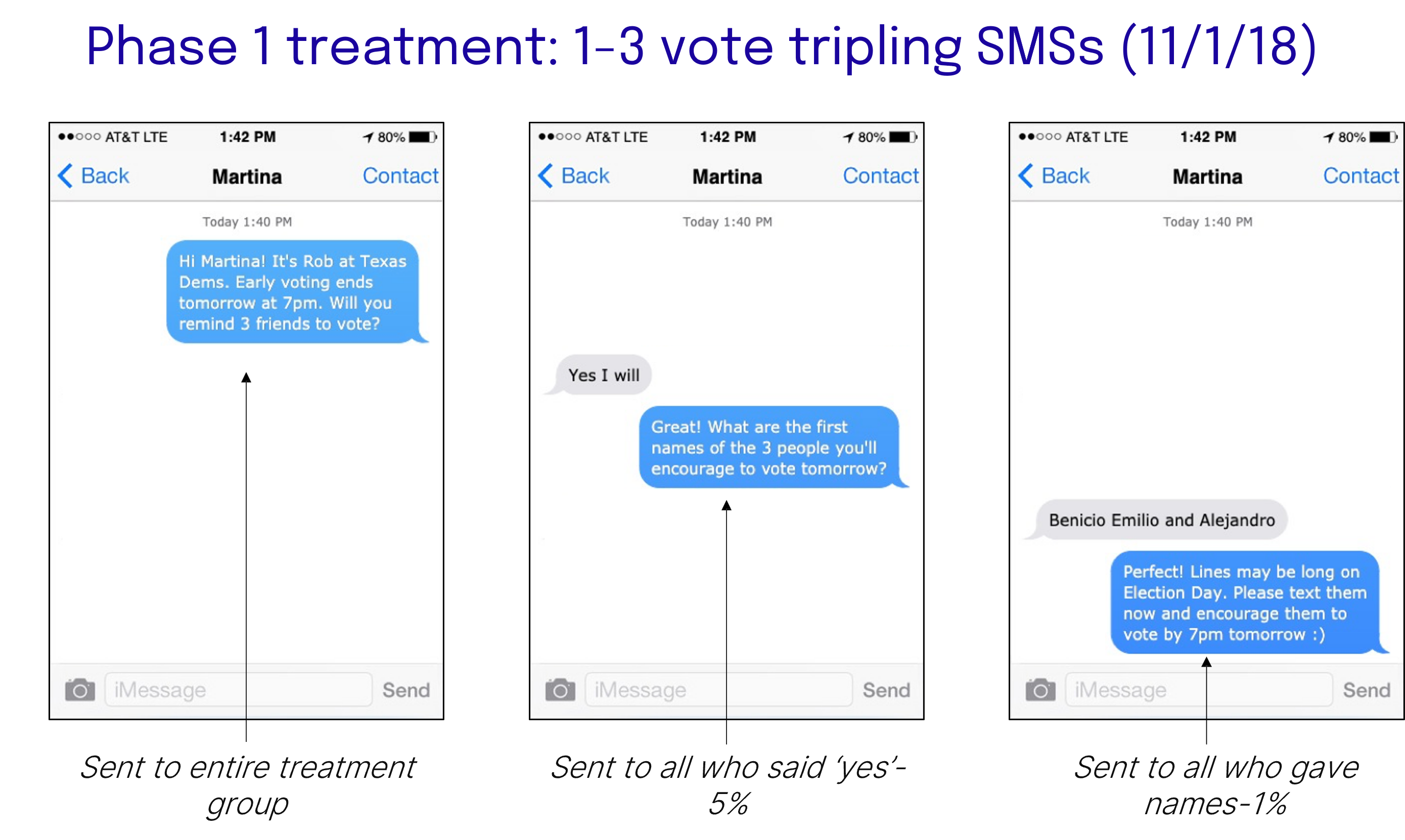

Wave 1: On November 1st, a text message was sent on behalf of the Texas Democrats reminding the target that early voting ends tomorrow and requesting that they “remind 3 friends to vote”. For the 5% of targets who responded affirmatively, a reply asked for the first names of the 3 friends to be mobilized. Nearly 30% of these individuals provided 3 names.

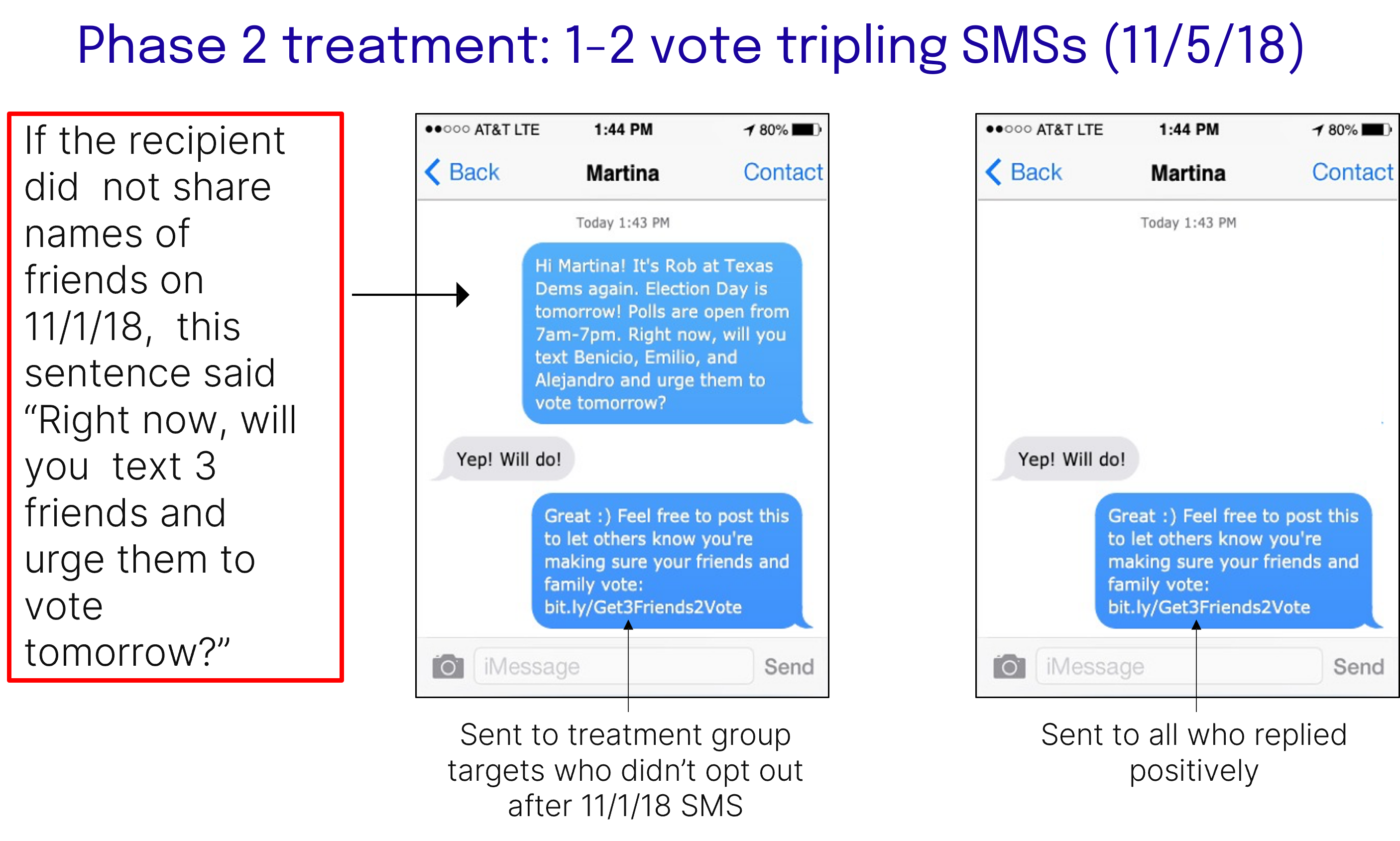

Wave 2: On Monday, November 5th, a text message was sent on behalf of the Texas Democrats reminding the target that Election Day is tomorrow and requesting that they “urge 3 friends to vote”. Those who applied affirmatively were thanked and asked to let friends know about their action on social media.

This texting campaign is light compared to normal campaign practices and highly unusual in that it targeted people who already voted and could not be mobilized themselves.

Outcome

After the election, official state turnout records were consulted to determine the turnout behavior of the roommates of targeted early voters. Because initial targeting was conducted via voter files, matching the individuals was straightforward.

Analysis

Regression analysis was performed that:

Clustered standard errors on the targeted early voter (i.e., the unit of randomization) to account for any similarities among roommates living with the same targeted voter;

Controlled for the vote history and demographic traits of both the targeted early voter and the roommates.

These choices alter the estimated effect of the program very minimally and are performed to accurately reflect the design of the experiment and maximize statistical power.

Results

Turnout among roommates whose targeted early voter was assigned to the control group was 29.7%, which makes it clear that the program successfully targeted people in need of mobilization. Turnout among roommates who targeted early voter was assigned to the treatment group was 30.8%. This difference of 1.1 percentage points is both statistically significant (s.e. = 0.0057, p < 0.06) and substantively very large. To put these results into context, see the Analyst Institute’s meta-analysis comparing the effectiveness of voter contact methods in midterm elections. However, a voter mobilization effect of 1.1 percentage points by simply sending a text to a roommate is large no matter how it is compared.

The fact that early voters often live with more than one non-early voter means this analysis understates the effectiveness of the campaign. The average targeted early voter lived with 1.3 roommates. Thus, sending 1,000 tests to targeted early voters creates roughly 14 votes (1000 * 0.011*1.3 = 14.3).

2: Unfortunately, the design of the experiment does not allow for estimates of the effect among people who responded affirmatively to the request to mobilize friends (i.e., a treatment-on-the-treated effect) because some people who did not reply may have taken the action anyway (i.e., the exclusion restriction may be violated).

Recommendations

One of the appeals of the Vote Rev model is that it offers organizations a very low cost and meaningful request to make from supporters who turned down requests for more demanding tasks. It should be emphasized that this experiment only measures a small facet of the Vote Rev program and not the effectiveness of the main thrust of the intervention -- the effect of friends sending texts to friends. While this experiment provides strong evidence that that effort is likely to be effective (how else were these roommates mobilized), further research is required to estimate the effect of the broader program.