Executive summary

Generally, Vote Rev advises campaigns to recruit vote triplers from among their universe of likely voters. A Senate campaign in Georgia, for example, would recruit vote triplers who are, themselves, voters in Georgia.

Another possibility, however, is to recruit triplers who are not themselves voters in a race’s jurisdiction. There are a couple of primary reasons a campaign or GOTV organization may do this:

The campaign/organization has especially promising triplers elsewhere. E.g., a national progressive membership organization has extensive and under-utilized subscription lists in safe states, who are likely to know voters in swing states; or, a Congressional campaign has lists of supporters from previous cycles who have moved away, but likely still have friends in the district.

The jurisdiction itself is saturated and the campaign needs to get creative. Consider, for example, Wisconsin Democratic voters in 2020: these voters will be getting dozens or hundreds of contacts before November, and will likely begin to tune out all manner of political outreach from strangers. A contact from a friend may be the only way to break through the noise.

Of course, the downside to external triplers is that there is no guarantee they know anyone in the target jurisdiction. There are, broadly, two solutions: (1) National-scale campaigns, or (2) Highly targeted tripler lists.

1. National-scale campaigns

According to recent research by Vote Rev, most Democratic voters in safe states have friends in swing states, whom they would be willing to remind to vote. We call these safe-state triplers.

Using Amazon Mechanical Turk, Vote Rev surveyed 337 Democratic and independent adults, of whom 90 were from one of the key presidential battlegrounds (AZ, FL, GA, MI, NC, PA, WI), and the remaining 247 were not.1 Respondents were asked:

Suppose a presidential campaign you support sent you a message that said, "We need your help to get out the vote in swing states (MI, WI, PA, FL, NC, AZ, GA). Can we count on you to remind 3 friends in these states to vote in November?" Would you be willing to do this?2, 3

Respondents answered “Yes,” “No,” or “I don’t have any friends in these states.” Those who answered yes were then shown:

Suppose the campaign then messaged you:

"Great! Every vote in a swing state counts. What are the first names and states of the 3 friends you would remind?" Please enter below the first name and state for each of the 3 friends. #1 Friend and State (e.g. "Carmen Michigan" or "Kyle FL"):

To mimic the experience of vote triplers being recruited via SMS, on the page where respondents entered these names and states, the original message with the list of target states remained visible.

1: The original sample contained 500 adults; 163 were screened out as ‘Lean Republican’ or ‘Strong Republican’ in response to a generic ballot survey.

2: Note that a previous version of this survey included only the state abbreviations and allowed respondents to select “I do not know what those abbreviations refer to.” Only 1.7% of respondents selected that option, suggesting that, overwhelmingly, Americans are familiar with state abbreviations. This version, however, also had lower reported opt-in, with respondents seemingly confused by the ask when it did not explicitly clarify why this list of states.

3: A previous version of this survey referred only to “swing states,” without explaining which states those were. In that version, while most voters seemed to indicate they knew what a swing state was, many respondents provided friends in non-pivotal states.

Table 1: Tripling rates and residency of friends

Table 1 shows results among these 337 respondents, and shows, in Column (3), that a little under one third of respondents in non-target states report not knowing any friends in the target states. Column (1) provides a different way of looking at the question: among prospective triplers who are from the target states, 78% are amenable to the tripling ask, while about 45-50% of safe state voters are amenable to the safe-state tripler ask.5 Column (3) roughly suggests that safe-state tripler sign-up would be about a third lower than regular tripler sign-up; Column (1) suggests safe-state tripler sign-up rates would be about 45% lower.

Among those who say they would have swing state friends to remind, the vast majority do indeed go on to name friends in swing states, although, oddly, not quite all. Only 90% of the six states named are those the text requests, and only 92% are swing states in any sense.6 (These ratios are consistent across triplers in both swing states and safe states.)

Roughly speaking, this analysis suggests that recruiting triplers in safe states to mobilize votes in presidential/senate battlegrounds is probably around one third to one half less effective than doing so in the target jurisdictions themselves. However, such a calculation does not take into account the vastly different organizing environments facing voters in safe and swing states. Previous research shows that vote tripling, like most turnout techniques, works better in less-contested environments, when the messaging has less to compete against. This dynamic is very much in play looking at safe and swing states in 2020: swing-state Democrats will be getting bombarded with hundreds of voter contacts, while safe-state Democrats will be relatively untapped. So, while safe-state tripling recruitment may be 30-50% less efficient in the abstract, it may well be significantly more effective given the relative media environments involved. While this countervailing effect is hard to quantify, it is hard to believe that safe-state tripler recruitment would not be at least commensurately powerful to traditional vote tripling tactics in swing states.

4: Any state perceived to be a presidential or Senate battleground. Virginia is arguably not a battleground anymore, but in the popular imagination it is often thought to be.

5: Note that this is consistent with self-reported willingness to triple in other online studies. In an earlier hypothetical tripling study conducted using Lucid panels, Vote Tripling found that 77% of respondents said they were “extremely likely” or “moderately likely” to triple in real life, and an additional 11% reported they were “neither likely nor unlikely.”

6: Other states named more than once are Alaska (2), California (13), Illinois (2), New Jersey (5), New Mexico (2), New York (5), Tennessee (2).

Which triplers know friends in swing states?

We asked respondents a battery of demographic questions in an effort to understand if certain voters would be better candidates to be safe-state triplers. In this analysis, there is an open question how to treat respondents who answer “no” — are they to be dropped, as the “no” is likely unrelated to the specific issue of knowing friends in swing states, or should they be included, since the “no” indicates something about openness to the ask? In Table 2, we present both versions. We also present models using a binary outcome (tripler==”yes”) and using the number of actual friends in pivotal states provided.

A few trends are clear among the sample of safe-state respondents:

Younger respondents are slightly more likely to be safe-state triplers, regardless of which outcome we use. The oldest voters are about 15-20 percentage points less likely to reply “Yes” to the tripler question than the youngest voters.

Respondents who are stronger Democrats are slightly more likely to be safe-state triplers. However, this shows up mainly in that fewer strong partisans reject the ask out of hand. When “No” responses are dropped, the effect becomes weaker and smaller.

Respondents who have previously lived in another state are significantly more likely to be safe-state triplers, especially when using the outcome of actually provisioning friends in the correct states. However, this relationship is much weaker when using recent residency in another state, which is all that voter file data usually contains.

Respondents who voted in 2016 are more likely to be safe-state triplers, and the relationship is especially strong when “No” responses are dropped. The correlation is generally missing for those who voted in 2018.

White voters are significantly more likely to be safe-state triplers, especially when “No” responses are dropped from the sample. (The reference category in this analysis for race/ethnicity is Asian.)

There do not appear to be meaningful trends around income, gender, or other races. Being in a state bordering a pivotal state is not a meaningful predictor of likelihood to be a safe-state tripler. (Regression not shown.)

Table 2: who agrees to be a safe-state tripler?

OLS regressions. t-statistics in parentheses *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

All told, the best candidates for safe-state tripling would appear to be younger voters who are strong partisans and voted in 2016. Voters who have lived in another state at some point in their lives are especially good candidates, but this association appears to be most meaningful when the out-of-state residency was more than 15 years ago, which makes the insight somewhat unactionable for campaigns. However, none of these trends are especially strong, meaning that organizations could do worse than just blanketing their usual universes in safe states.

In which states do triplers have friends?

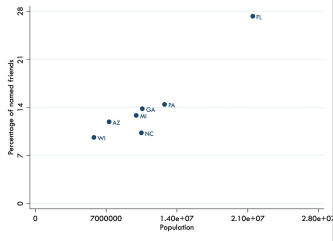

Triplers provide friends in the target states almost exactly in proportion to those state’s populations.

Figure 1: States of selected friends and state populations

There is some evidence that triplers are more likely to select friends in neighboring states. Triplers in states neighboring AZ, MI, WI, and PA are significantly more likely to select friends in those states than other triplers. (This relationship does not hold for Georgia, Florida, or North Carolina.) Recall, however, that being in a border state does not seem to influence whether a respondent is willing to be a safe-state tripler — simply in which state she selects friends.

2. Highly-targeted tripler lists

More geographically targeted campaigns and organizations do not have the luxury of using the above approach. While the DSCC or a presidential campaign would be satisfied to produce tripler contacts in any of 7-15 states, most campaigns need to yield contacts in a single state or a single district; and there is no evidence that the average safe-state Democrat has friends in any particular state or district.

In these instances, savvy campaigns and organizations could take advantage of more nuanced data to produce external tripler reminders. For example, supportive voters who lived in the district during a previous cycle and have since moved out could be good targets for tripler recruitment. This may be especially true with special cases like college students, who may still have ties to their old campuses. Campaigns or organizations could pull lists of former-resident voters with high partisanship and engagement scores, and attempt to recruit specialized triplets from these populations, e.g.:

“Hi [name], it’s [name] from the [campaign name]! Thank you again for supporting [candidate] in 2018. Our records show you’ve moved in the last couple years, but we’re facing a tight race and we could still use your help getting out the vote this cycle. Can we count on you to remind 3 friends back in [former town of residence] to vote this November?”

Vote Rev has not yet piloted this approach, but the targeted nature of the contact could yield dividends.