HNPC - Message Testing Results

Insights from a Prolific survey experiment

Introduction

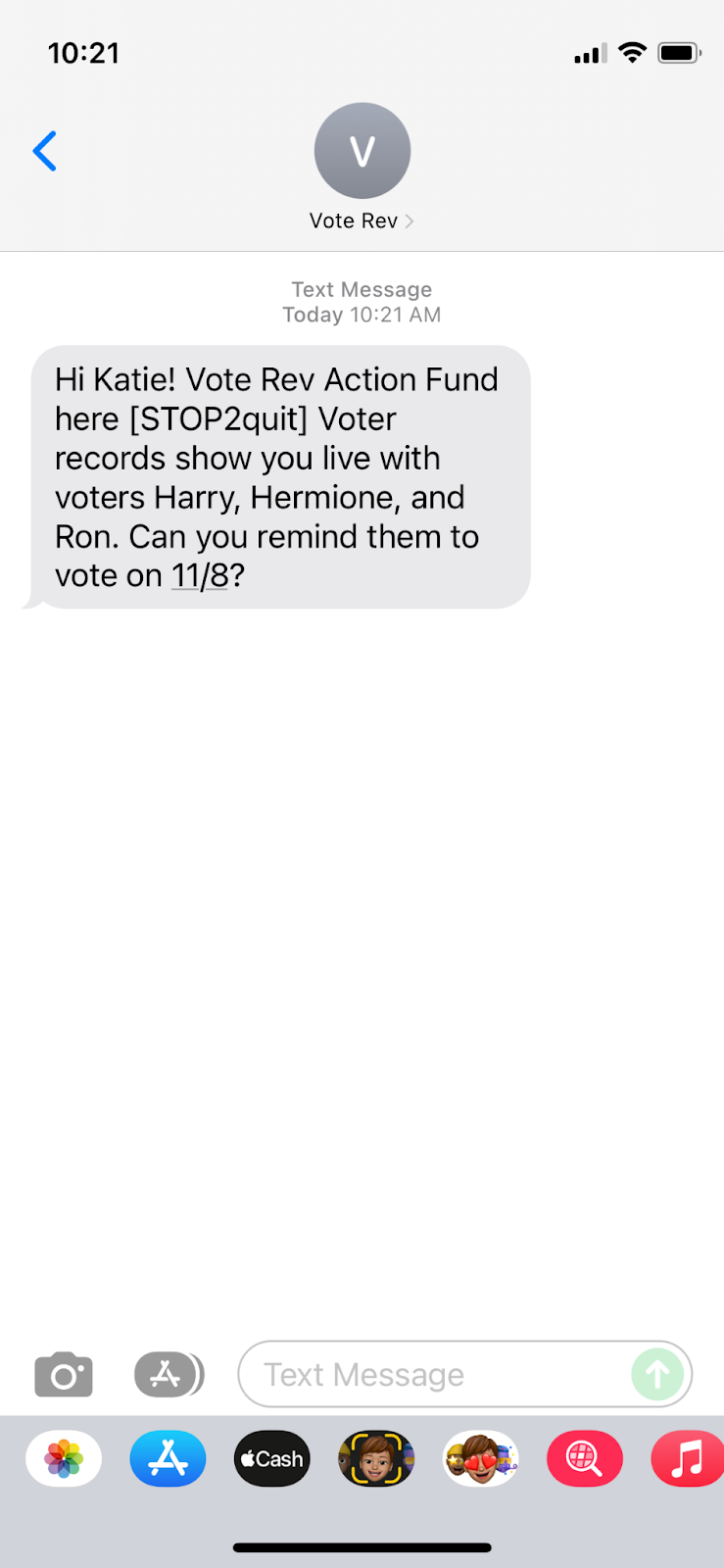

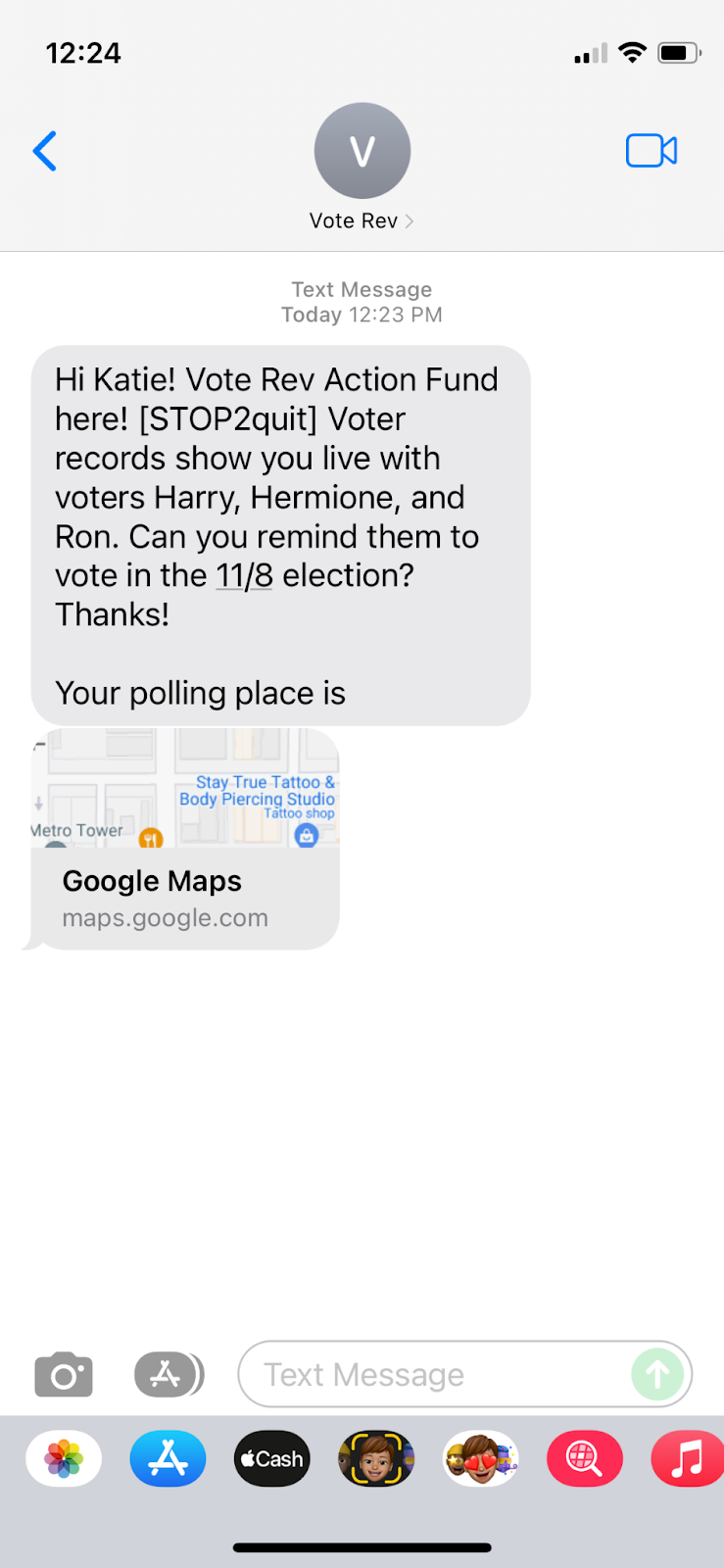

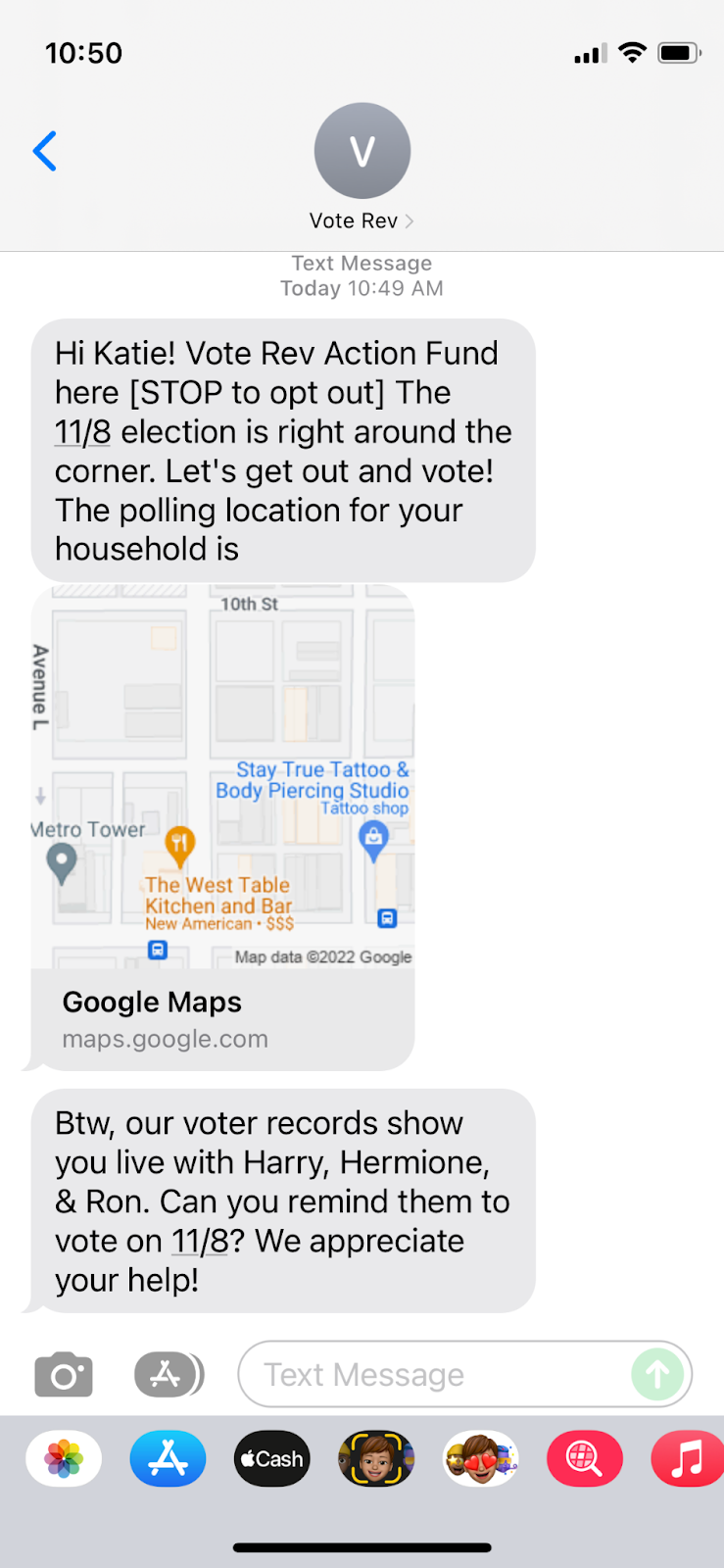

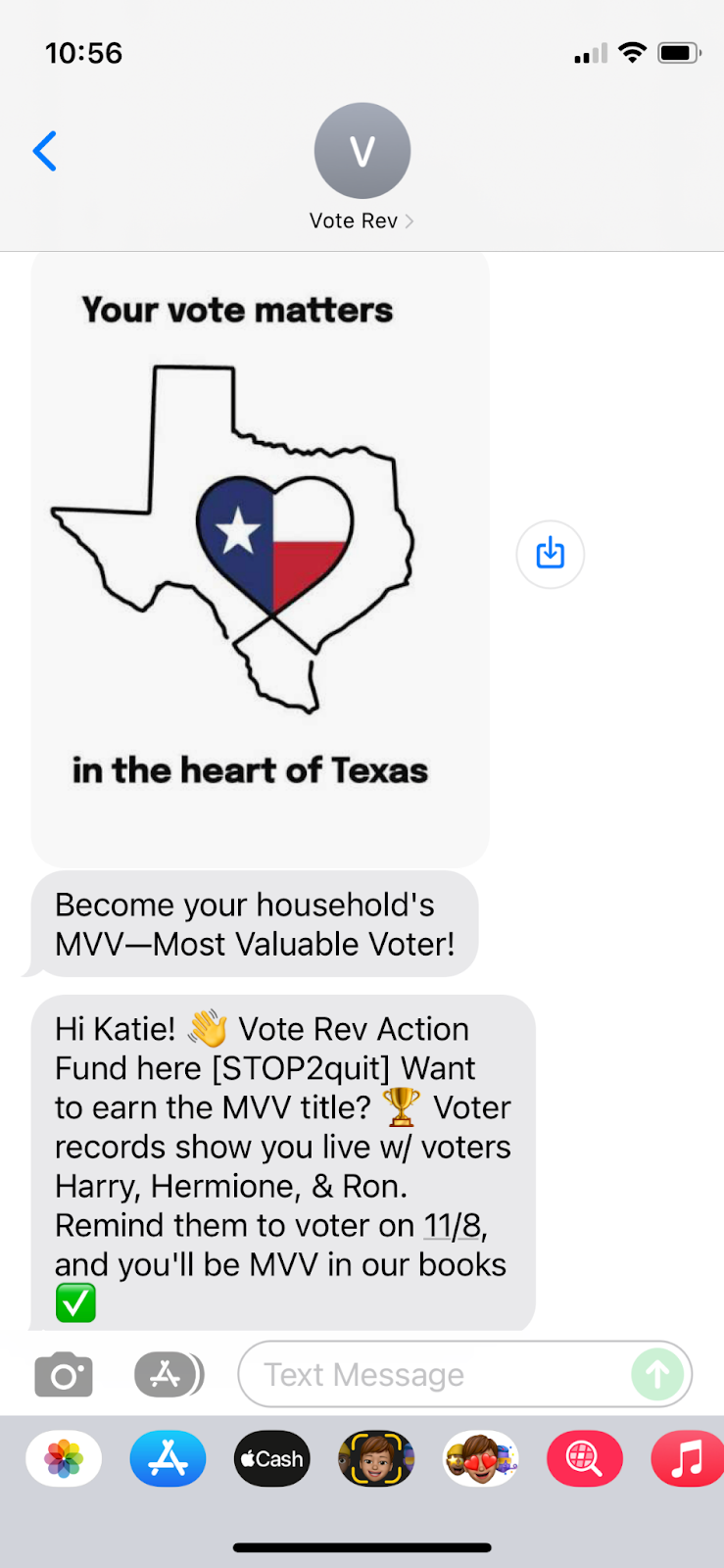

Previous Housemate Naming Pledge Collection (HNPC) tests have had mixed results. To optimize the efficacy of the SMS intervention that we will use in our November 2022 midterm election trial, we hired a copywriter to draft texts and a graphic designer to create an image. We tested on Prolific four messages: (1) a basic text message (similar to the one used in the 2022 TX primary trial) that served as a control condition, (2) an enhanced message including polling location information (polling info), (3) a foot-in-the-door double-text sending first the polling location and then asking people to remind their housemates to vote, and (4) a creative text including an image and emojis. Results show that people receiving text messages including polling location (both 2 and 3) said they would be less likely to opt out of receiving text messages and would be less annoyed by receiving text messages than the control message. People that received the creative text message were less likely to report being creeped-out if they received the text message.

What we did

Between September 16 and 19, we recruited 1,358 participants on Prolific to answer a survey. Participants were recruited from Prolific’s pre-existing pool of respondents and were limited to people that had previously stated they are US citizens and identify as being Hispanic or Latino, Black or African American, Asian, Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, or Native American. Participants were paid $2.50 for about 2.5 minutes of their time. Our resulting sample was on average 32.3 years old (std. dev,=10.3), 46% identified as women or non-binary, the median and modal educational attainment was college or more, and the median income category was between $52,000 and $85,000.

The survey first asked respondents a battery of demographic questions. After, respondents were asked to analyze a hypothetical situation in which they received a text shown in a screenshot. The screenshot was randomly selected from four options, each corresponding to one of the text messages described above. The screenshots can be found in the Appendix.

Finally, respondents answered a series of questions asking respondents how they would feel and react if they received a similar text message themselves. Specifically, respondents were asked on a 7-point Likert scale the following questions:

If you received a text message like this, how likely would you be to reply at all? (where 1 means definitely would not respond and 7 means definitely would respond)

If you received a text message like this, how likely would you be to remind your household members to vote? (where 1 means definitely would not remind them and 7 means definitely would remind them)

If you received a text message like this, how likely would you be to opt out of receiving future text messages from our organization? (where 1 means definitely would not opt out and 7 means definitely would opt out)

If you received a text message like this, how would you feel? (where 1 means extremely negative and 7 means extremely positive)

Participants were also asked to select which emotions they would feel from the following list: happy, encouraged, empowered, surprised, angry, annoyed, frustrated, sad.

Results

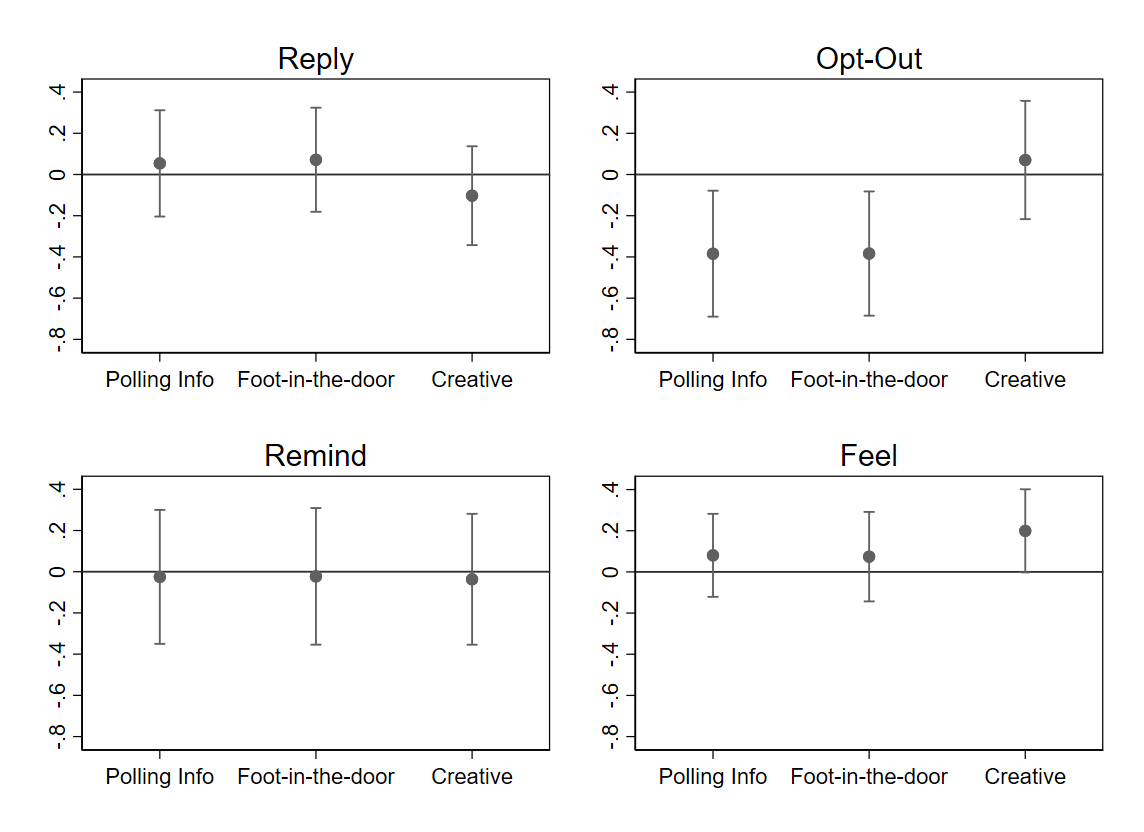

Our main results are shown in Figure 1. It presents point-estimate and 95% confidence intervals of the treatment effect (as compared to the basic text) of the polling info, foot-in-the-door, and creative treatments, estimated via OLS regressions with heteroskedasticity robust standard errors and controlling for demographic covariates, on our main outcomes: whether people would reply to the text, whether they would remind their friends to vote, whether they would opt-out of receiving communications, and whether they would feel negatively or positively about the text.

The results show that there is no evidence that the different texts affect participants’ willingness to reply to the texts or to remind their housemates to vote. However participants in the polling info and foot-in-the-door condition were both, on average about 0.38 points less likely to opt-out from receiving our text messages (p=.013 for poll info and p=.014 for foot-in-the-door) than those in the basic condition. Participants in the creative condition reported on average feeling 0.2 points more positive than those in the basic condition (p=.053).

Figure 1. Effect of Treatments on Main Outcomes

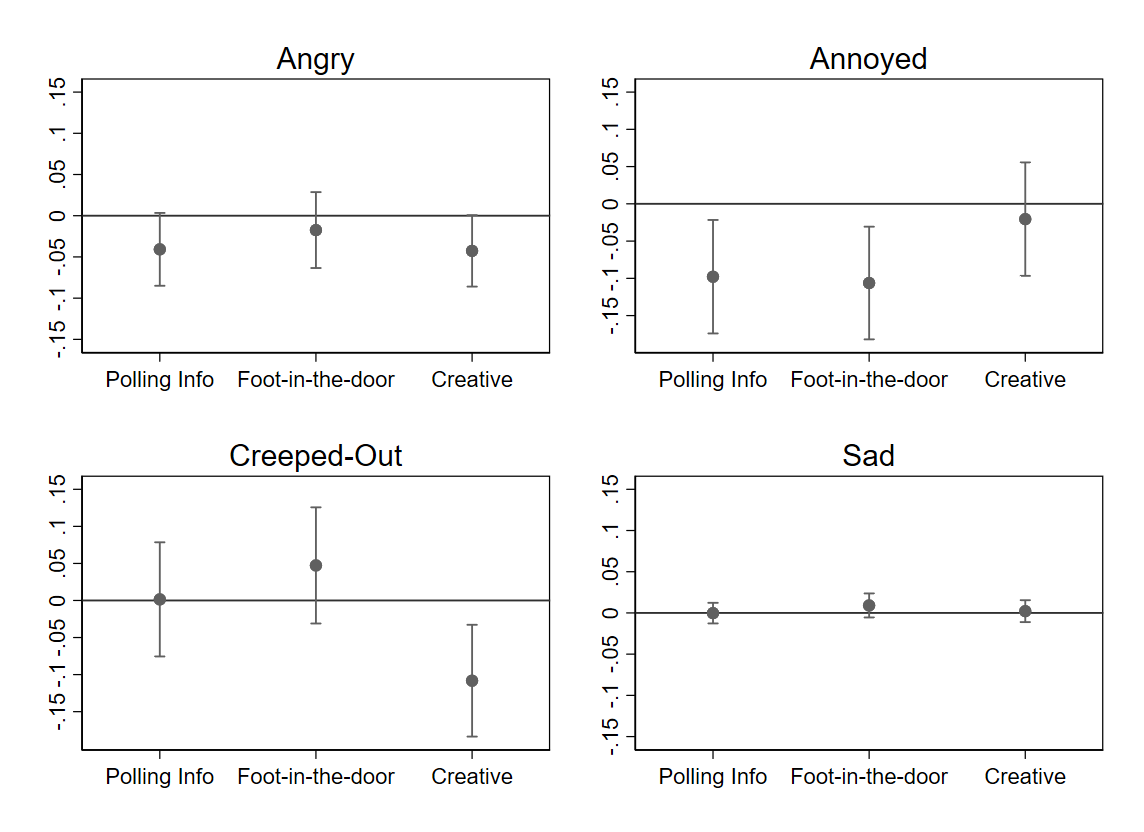

Figure 2 reports our findings on the emotions that people said they would experience if they received a similar text. The findings show that people in the polling info and the foot-in-the-door conditions were significantly less likely to say they would be annoyed (about 10 percentage points, pp, for both, p=.012 for polling info and p=.006 for foot-in-the-door) than those in the basic condition. People in the creative condition were about 11 pp (p=.005) less likely to say that they would be creeped-out than those in the basic condition. Finally, there is some suggestive evidence that people in the polling info and the creative condition would be about 4 pp less likely to feel angry than those in the basic condition. (p=.070 for polling info and .054 for creative).

Figure 2: Effects on experienced emotions

Conclusion

Though was no difference in the likelihood of replying or reminding one’s housemates to vote with a basic text message, messages including polling place information and images/emoji resulted in a lessened likelihood of opting out and in a better experience for recipients, respectively, making them an attractive alternative for using in our trials.